The Birth of a baby is the most precious gift to a parent. And in this, parents, want to do what is best in them and protect them from harm.

The initial contact with healthcare professional after our babies come into this world, is the recommendation to give them vaccines. We are told that vaccines will protect them from most common ailments that attack children while growing up like; pneumonia, bloodstream infections, meningitis and other serious infections. The United Nations Millennium Development Declaration address among many the Millennium Development Goal No. 4; to reduce Child Mortality. Vaccines play a significant role in this achievement.

Within hours of birth, children will get a shot of the hepatitis B vaccine. At around 2 and Half months of age, children could get as many as five separate shots containing seven vaccines accompanied with Oral Vaccines.

For a parents, all of these shots can seem overwhelming. For many parents, they would ask:

- What are vaccines?

- How do vaccines work?

- What is my child’s risk of getting one of the diseases that vaccines prevent?

- Are vaccines safe for my baby?

We will describe how vaccines are made and how vaccines work to protect our children from harm. With a better understanding of vaccines and the diseases they prevent.

This will therefore help you see why your doctor/nurse feels so strongly about recommending vaccines to your precious gift.

HOW DO VACCINES WORK?

Vaccines give immunity without making children suffer the high price of natural infection.

What is Immunity?

A condition of being able to resist a particular disease especially through preventing development of a pathogenic microorganism or by counteracting the effects of its products.

Because chickenpox caused occasional hospitalizations and deaths in children, a vaccine was made to prevent it.

The chickenpox (or varicella) vaccine, like all vaccines, separated the part of the chickenpox virus that made children sick (the pathogenic or virulent part) from the part that made them immune (the immunogenic part).

The chickenpox vaccine was made by taking natural chickenpox virus and growing it in specialized cells in the laboratory. As the chickenpox virus got better and better at growing in these laboratory cells, it got worse and worse at growing in children.

The chickenpox vaccine represents the better of two worlds. On the one hand, the vaccine grows well enough to cause immunity. On the other hand, it doesn’t grow well enough to cause disease.

Therefore, children can get immunity to chickenpox without having to suffer the potentially high price of natural infection.

All vaccines are made using a principle that separates the part of the virus or bacteria that makes you sick from the part that makes you immune.

Common Questions and Concerns About Vaccines

Are vaccines safe?

To best answer this question, we must first define what we mean when we say “safe.” If by “safe” we mean completely risk-free, then vaccines aren’t 100 percent safe. Like all medicines, vaccines have mild side effects, such as pain, tenderness or redness at the site of injection. And some vaccines have very rare, but more serious, side effects.

But nothing is harmless. Anything that we put into our bodies (like vitamins or antibiotics) can have side effects. Even the most routine activities can be associated with hidden dangers. So a more reasonable definition of “safe” would be that the benefits of a vaccine must clearly outweigh the risks.

Do we still need vaccines?

Vaccines are still given for three reasons:

- First, for common diseases (like chickenpox, pertussis or pneumococcus), a choice not to get a vaccine is a choice to risk natural infection. For example, every year thousands of children are infected with pertussis and some die from the disease. Therefore, it’s important to get the vaccine.

- Second, some diseases (like measles, mumps or Hib) still occur in the United States at low levels. If immunization rates drop, even by as little as 10 to 15 percent, these diseases will come back.

- Third, while some diseases (like polio, rubella or diphtheria) have been either completely or virtually eliminated, they still occur in other parts of the world. Polio still commonly paralyzes children in Africa, diphtheria still kills children in Russia, and rubella still causes birth defects and miscarriages in many parts of the world.

Because international travel is common, these diseases are only a plane ride away from coming back into any country in the world.

Are children too young to get vaccines?

If infants aren’t too young to be permanently harmed or killed by viruses or bacteria, then they aren’t too young to be vaccinated to prevent those diseases.

The diseases that vaccines prevent often occur in very young infants.

For example, before vaccines, thousands of young infants were hospitalized or killed by diseases like whooping cough, bloodstream infections (sepsis), meningitis and pneumonia — diseases that can now largely be prevented by vaccines.

The only way to keep young infants from getting these diseases is to give them vaccines soon after they are born.

Fortunately, infants given vaccines in the first few months of life are quite capable of making a protective immune response.

Can children manage so many different vaccines at the same time?

The mother’s womb is essentially a sterile environment. The fluid surrounding the baby is free from bacteria.

However, within minutes of leaving the womb, the child must confront thousands of bacteria. By the end of the first week of life, the child’s skin, nose, throat and intestines are covered with tens of thousands of different bacteria.

Fortunately, from the moment of birth, infants begin to develop an active immune response to these bacteria — an immune response that prevents these bacteria from entering the bloodstream and causing harm.

The vaccines that children receive in the first two years of life are just a drop in the ocean when compared to the tens of thousands of environmental challenges that babies successfully manage every day.

Do vaccines weaken the immune system?

Sometimes infections with natural viruses can weaken the immune system. For example, children infected with influenza virus are at risk of developing severe bacterial pneumonia.

Also, children infected with chickenpox virus are at risk of developing severe infections of the skin caused by “flesh-eating” bacteria.

However, because the bacteria and viruses contained in vaccines are highly weakened versions of natural bacteria and viruses, they do not weaken the immune system. On the contrary, vaccines prevent infections that weaken the immune system.

Can’t we give vaccines by a method other than shots?

Viruses and bacteria usually damage children by first entering the bloodstream.

So, the best way to fight off these infections is to make antibodies that are present in the blood.

By giving vaccines as shots, we ensure that the body quickly makes antibodies in the blood.

For example, diseases like hepatitis B and chickenpox can be prevented by giving a vaccine even after a child is exposed to these viruses.

This is because antibodies in the bloodstream are made more quickly after vaccination by shot than they are made after natural infection.

Can vaccines cause long-term diseases like multiple sclerosis, diabetes, hyperactivity, autism or asthma?

When one event precedes another, we often wonder whether they are related.

For example, some people who smoke a lot of cigarettes get lung cancer. But “Does cigarette smoking cause lung cancer?”

Because vaccines are given to almost all children, many children with diseases like autism, asthma or hyperactivity will have received vaccines.

And some of these children will have received vaccines recently. The question is: “Did the vaccine cause the disease?”

What we do know is that vaccines don’t cause autism, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, allergies, asthma or permanent brain damage

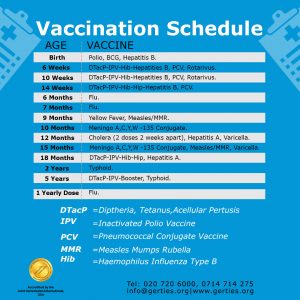

Vaccination Schedule